- Home

- David Athey

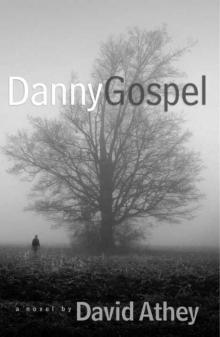

Danny Gospel

Danny Gospel Read online

Advance Praise for Danny Gospel

"Sorrow and joy are at the wheel in a wild ride on the back roads of Iowa and beyond. Climb in, hang on, and hope."

Paul J. Willis, author of Bright Shoots of Everlastingness: Essays on Faith and the American Wild

"Danny Gospel lingers like a dream, as poignant as Danny's search for a normal, happy life, which is as elusive as it ought to be, as it must be."

Michael Larson, author of What We Wish We Knew

"Danny Gospel is as compelling and engrossing a read as I have had lately. Written in the tradition of Holy Fool stories, Danny will humble your heart and invite your soul to reconsider some of its assumptions."

Phyllis Tickle, author of Shaping- of a Life

"The imagery and descriptions of nature within this work are rich and vivid. Athey is a true master of the English language. This novel is an instant classic."

Jess Moody, author of Club Sandwich and A Drink at Joel's Place

"If song is the doubling of prayer, as the saying goes, then Danny Gospel, in singing the story of a life, transmutes it into a prayer and draws the reader's life too into that full-voiced song and prayer charged with the power of praise and grace."

Seraphim Joseph Sigrist

"David Athey has written a Gospel novel, and not merely because of its title. It is a dreamlike and mystical narrative that takes us inside the mind and life of a Christian who has sought to seize the Kingdom in the midst of sorrows and failures. At a time when much so-called "Christian" fiction is obscenely sentimental, Danny Gospel is a bracing and honest book."

Ralph C. Wood, author of Flannery O'Connor and the Christ-Haunted South

"What is a song? It is a perfectly expressed emotion. It is words that dance. It is a place one returns to again and again, like a rhyme, like a home. It is a cry to heaven. Danny Gospel is a song. David Athey sings it."

Dale Ahlquist, President, American Chesterton Society

"We all know, whether we know it or not, what a good novel is: it's the one we don't want to stop reading, the one we don't want to end, and that is true of Danny Gospel. For those who love language this work is a feast....

"Although there is a good deal of humor in it, one cannot read it without thinking deeply about life, faith and the struggle to believe in a saving God of power and love. Danny Gospel is the best American novel deliberately written from a Christian perspective."

Professor James B. Anderson, St. Cloud State University

"Danny Gospel is a tale charged with sorrow and suffering and hope and beauty. From the very first chapter, you will be whisked into a world of vivid detail, into a surreal existence in which every turned corner offers a sense of mystery. A cast of peculiar and diverse characters and a series of well integrated flashbacks help to unravel Danny's winding road to redemption."

Skylar H. Burris, Editor, Ancient Paths Literary Magazine

"Magical, mythical, profound, Danny Gospel takes us from the lost family farms of Iowa to the lost beaches of Florida and manages to cover everything: faith, doubt, kindness, cruelty, redemption and passion."

Faith Eidse, Ph.D., co-editor, Unrooted Childhoods

"The Great Old Truths don't change. But from generation to generation we need to hear them from new voices speaking in new ways.... This is a wonderful, valuable book, a joy to read, and a wonderful song to know our lives are part of."

Dr. Jack Hibbard, English Department, St. Cloud State University

a n o v e l

David Athey

To Kathleen Anderson, Dave Long, and everyone else who helped with this novel.

Thank you for believing.

-DA

chap one

WE PLAYED OUR first concert by torchlight near the river. Free of charge, our old-fashioned act attracted a crowd to the hymns and spirituals that most people know by heart. "Amazing Grace," "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," "Kum Ba Yah," "I'll Fly Away" .. .

My father, an ex-marine, was a Johnny Cash look-alike. He stood tall yet slumped in a black suit and wailed baritone. I stood next to him and added my ten-year-old voice to the cause. Grandmother, in a white Sunday dress, sat on a stool and strummed a sweet guitar. Jonathan wore jeans and a T-shirt and strutted with his banjo, grinning at the girls. Holly, our little tomboy princess, joyfully fiddled an old violin. And Mother, so mythological with her long black hair wisping to the ground, plucked the crowd skyward with her Celtic harp.

That summer of 1986, we performed free concerts all over Iowa-at fairs, festivals, and churches. And we became so famous that people began forgetting our family name. Everyone started calling us the Gospel Family.

On nights when there were no concerts, we gathered on our porch and sang to the fireflies under the stars. And I believed the songs about the Promised Land were really about our farm.

Fifteen years later, the farm was just a memory and everyone in my family was dead, except for my brother, who rarely spoke to me. I was living in a trailer park in Iowa City and working as a mail carrier, delivering so much junk and so many bills. Every morning I met college girls traipsing off to class, the intelligence of God apparent in their walking, as if their graces could keep the world forever spinning in ecstasy. I was miserable, and went home after work and read books about hermits in the woods, monks in the cliffs, and warriors of prayer in the desert. One story that struck me was about a young man who wanted to shine. He sought out an elder who lifted his hands like tree branches to the sky, fingers glowing like candles. The elder challenged the young man, "Why not become all fire?"

I scribbled in the margin of the book: God is light.

Carrying the mail was relatively easy, and almost every day I was offered fresh baked goods-cookies, bars, brownies, and cupcakes-from apron-wearing ladies who greeted me at their doors. Because of so many sugars, I soon gained a grunting weight and had to put myself in serious training. Every night in my living room, I did hundreds of sit-ups and push-ups, followed by a strenuous reading of the lives of skinny, fiery lovers of God.

After showering, I'd collapse into bed and stare up at a mural of the Garden of Eden that I'd painted on the ceiling, the colors softly glowing in the dim light from a nearby streetlamp. I'd stare for hours and hours, wondering: why would anyone give up Paradise?

In the mornings, bleary-eyed, I'd crawl out of bed and deliver the mail. The junk and the bills. More junk and more bills. Even the greeting cards in their festive envelopes made me depressed. I forced smiles for the apron-wearing ladies and their gifts of baked goods, and they looked at me with pity, because it was obvious that I wasn't living a real life.

One clear windy day with red-orange autumn leaves swirling into the sky, Mrs. Henderson gave me a sprinkle cookie, and asked, "Danny, why don't you start another gospel band? Why not play with your brother?"

I answered, "I don't sing anymore. Thanks for the cookie. Here's your mail."

At the age of twenty-five, I felt lost and worthless, walking in circles, day after day, enduring the sweet old ladies, the traipsing college girls, and the whims of every sort of weather. I moped home after work, opened books about holiness, and then sweated through my exercises, making my body suffer. And I always prayed, deep into every night. Flat on my back in bed, with a luminous Adam and Eve looking down from the ceiling, I repeatedly asked for the same old thing: a normal happy life.

It didn't happen, and it didn't happen, until that morning in October 2001, when she appeared in my bedroom.

She was an average woman, perfectly lovely, dressed in white. She leaned down and kissed me lightly on the lips. Trembling, I wondered: is this normal and happy, or just a dream? The woman said something wonderful with her eyes. I reached up to touch her face. I whispered, "Are you-"

She disappeared

from the room.

And I had to follow her.

I pulled on a pair of jeans, forgetting about shoes and a shirt, and rushed out into the sunrise. Where could the woman be hiding? She wasn't in my front yard. She wasn't in my backyard. Smiling, enjoying the chase, I climbed into my pickup and searched around the trailer park. Nothing. No sign of her. Yet I could still taste the kiss, and it felt stronger when I sped out to the shimmering cornfields, and I believed that my life was like a favorite book now turning to the happiest chapters. And I imagined a heavenly wedding, and everything in the world was like the first day of creation, as if every death specter that had plunged into me since baptism had been kissed clean away.

And then a hog truck appeared. The rig was covered with mud and filth, about to crash into me. A prayer for help arose in my heart but it couldn't get to my lips in time. Nevertheless, the hog truck swerved around me and into the ditch while I hit the brakes and skidded to a stop. I jumped out of my pickup and saw, through a cloud of golden dust, a herd of swine escaping from the back of the trucker's rig.

I called out to the driver, "C'mon, we can catch them."

"No," he said, not leaving his seat. "Let those pigs fly. The loss will be a good tax break."

"Don't be crazy," I said, pointing at the cornfield. "The herd could cause a lot of damage."

The truck driver lit a cigarette and added smoke to the cloud of dust. "Let those pigs fly," he said, "and mind your own business."

Driving away from the scene of the accident, something told me that I should go into town and put on my uniform and report to the post office. Something told me that if I denied the kiss and the woman in white, then I could keep my job and salvage the life I'd been living.

"Salvage?" I whispered as I sped down the road. "What's left to salvage?"

Looking heavenward, I was startled to see so many birds. Above the yellow fields, the blue sky was filled with birds of many feathers, drifting and circling, inspiring me to sing my favorite spiritual: "I got wings, you got wings. All of God's children got wings. When I get to heaven, gonna put on my wings. I'm gonna fly all over God's heaven."

Not paying attention to the earth, I plowed into a cornfield.

The truck was stuck, half buried, the stalks so thick and strong that my door wouldn't open. I had to squeeze through the window, my ears getting tickled by the ears of corn; and then I found myself face-to-face with a deer. The twelve-point buck was staring at my bare chest, as if thinking: man, are you okay?

I was better than okay. Because of the kiss, every nerve in my body was a solar flare. My heart was a pulsar.

"Mr. Deer," I said. "Would it be possible for you to run into town and find a tow-truck driver?"

The old buck leapt away, in the opposite direction of town.

Well, I thought. I better find a telephone.

That should have been a simple task: to walk barefoot to the nearest farmhouse and borrow a phone. And away I went, treading lightly on the gravel road between the fields. Mile after long, lonely country mile, I searched for a house and saw nothing but corn.

When I was a little kid, even the larger farms had a sense of being part of a neighborhood, but now the land was looking more and more like an ocean of golden sprawl. I walked for at least an hour, eventually forgetting about finding a phone, thinking instead about trees, picnics in the shade, and old friends who understood what it meant to be a neighbor.

Finally, rising out of the sea of corporate corn, there appeared an island of perfect acres, a small farm consisting of bountiful patches of pumpkins and squash, an aspiring apple tree, and a wonderful scattering of yellow and orange chrysanthemums. Scratching around the flowers was a flock of cloud-white chickens.

I whispered, "Whoever lives here knows how to live."

I ambled up the dirt driveway to the farmhouse. On the porch was a solid-oak rocking chair, like the one my grandmother loved. Grammy Dorrie spent one hour each day on the porch, in every kind of weather, rhythmically watching the world.

One autumn afternoon, I stood beside her while she rocked, and I wondered if she saw something that my eyes couldn't see. I stood beside her for a long time, staring down the driveway.

Maybe she's waiting for Grandpa, I thought.

But I didn't say what I was thinking, because Grandma was a Baptist and Grandpa was in the grave, and Baptists don't believe in family visits from the grave.

Grammy took off her glasses, breathed deeply on the lenses, and cleaned them in the folds of her apron. She returned the glasses to her face and gazed longingly at the road.

And I left her alone with her secret.

Now on the morning of my kiss, at a farmhouse like my childhood home, the door opened and I turned from the rocking chair and saw an average, perfectly lovely woman. She was wearing a white peasant dress. Could it be? Was this her? The one I'd been searching for?

The woman said, "Hello. Where's your shirt?"

"I'm sorry. My truck broke down in the corn, and-"

"The corn stole your shirt?"

"Well, um, no. I guess I never put one on this morning. You see-"

"You're wounded," she said, staring at my chest.

"Yes. A long time ago."

The woman stood expectantly, waiting for me to explain how I got a scar over my heart in the shape of a cross. I just stood there, playing dumb, waiting for her to change the subject.

"Sorry to stare," she said. "I've never seen a scar like that."

"That's okay. May I please borrow your phone?"

The woman smirked warmly and handed me her cell phone. "Here. Call your therapist while I go find some flannel to cover you up."

"Thanks."

I sat in the rocking chair, leaned forward and back, took a deep breath, and dialed the gas station. "Grease, I need your help."

"Danny," he said, "where the heck are you? At the post office?"

"Listen," I said, rocking more quickly, "I'm out in the country. My pickup is stuck in a cornfield about a mile north of Saint Isidore's."

"Okay," Grease said, yawning, "here I come. You're lucky I'm not busy today."

"Thanks, Grease. I owe you."

"That's right. You never paid for your last tank of gas. What's with that? I thought mailmen were rich from stealing people's birthday cards."

"Shut up, Grease."

The woman returned with a man's shirt draped over her arm.

"My ex-fiance, Ethan, never liked flannel. Or work boots. Or having to kill things. You should have seen Ethan the first time I butchered a chicken. He got the heaves and started flapping his arms. And he started clucking. Clucking! How crazy is that? Anyway, I'm Melissa."

I arose from the rocking chair. "I'm Danny."

"You look familiar," she said. "I've seen you somewhere. You were fully clothed."

"Maybe you saw me delivering the mail in town."

"No," she said, tapping her fingers against her thigh. "But I have seen you before. I'm positive."

"Well," I said, "thanks for letting me use your phone. And thanks for offering the flannel. I'm a big fan of flannel."

Melissa gave me the shirt and I gave her the cell phone. Our fingers lingered for an electric moment as we made the exchange, and I thought: hmm, could she be the one who kissed me?

Melissa was tall and strong. Her hair was short and dark, and she spoke with a half-laughing voice. "This shirt was too big for Ethan. He had such narrow shoulders, and his arms were different lengths. And his poor head. It was asymmetrical! Our children would have been freaks. This farm would have become a circus."

I started to put on the shirt and hesitated because the fabric felt scratchy against my sunburned skin.

"Danny," she said, "if you're feeling shy, I can turn around while you get dressed."

"Okay. Thanks."

I struggled to pull the flannel over my flesh, but the shirt was too small. I couldn't even button a single button. So I said, "This isn't going to work," and gave the shirt back.

<

br /> Melissa laughed. "Sorry, Danny. Ethan was one of the little people. Anyway, you wanna stay for lunch? I could butcher a chicken. Are you hungry? Would you like to have some lunch? Forgive me for blurting this out, but are you seeing anybody?"

"I am hungry, Melissa. And I would like to stay. But, truth be told, I saw somebody in my bedroom this morning."

Melissa raised an eyebrow. "This morning? You don't seem like that kind of a guy."

I thought: what kind of a guy am I? Why am I flirting with this woman who isn't the woman of my dreams? "You're Danny Gospel," Melissa said. "Now I remem-

ber. I saw your family perform in Riverside Park. I was very moved by the music. Are you sure you can't stay for a while?"

I shook my head. "No. I can't stay."

Melissa shrugged. "Well, come visit again sometime. I'll butcher for you."

"Okay, that would be sweet," I said, and then hurried away from her farm.

The cool air, burning sun, and a swarm of mosquitoes fought over my skin while I jogged over the gravel. My bare feet were bleeding when I arrived at the cornfield where the pickup got stuck. Grease was standing there waiting, having already hoisted the Chevy. Good old Grease, with his big flat nose, pink ears, and great girth of gut. He was always dressed in dirty clothes, and he wore a dirty cap over his greasy comb-over. He was perhaps the dirtiest man on earth, but he'd been my good friend since childhood.

"This morning," he said, belching, "I was hung over from too many beers and three cans of beans. But at least I had the sense to put on a shirt and go to work."

I shrugged my red shoulders. "It's a long story." Grease raised his unibrow. "Is there a woman in the story?"

"Yeah, buddy. I'm getting married."

Grease lowered his unibrow. "What?"

"I'm getting married. On Christmas Eve."

Grease snorted. "That's a fantasy."

"No, it's holy matrimony, and she already has a dress picked out."

Grease slapped his greasy thigh. "What did you do, order a woman from the Internet? I'm tempted to order one myself. I've been saving up."

Danny Gospel

Danny Gospel